By: Victor Pinera

A proposed Illinois state amendment aims to broaden the statutory definitions of “violent video game” and “serious physical harm,” prohibiting the sale of video games portraying violence and motor vehicle theft.[1] This proposal comes in response to the increasing number of carjackings in Illinois communities, with Chicago Police Department reporting 1,417 carjackings in 2020—more than double 2019’s numbers—and 218 carjackings in January 2021 alone.[2] Illinois House Bill 351 aims to combat Illinois’s rise in violent crime at what Rep. Marcus Evans considers to be the core of the issue—the youth’s consumption of video games depicting violence and motor vehicle theft.

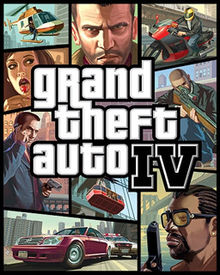

South Side state representative Marcus Evans Jr. proposed this amendment due to his growing concern over the wellbeing of his communities and the standards set in American society.[3] He was contacted in January by Early Walker of Operation Safe Pump, a 30-day operation which stationed private security guards at high-risk gas stations around Chicago.[4] Walker contacted various state legislators in an effort to ban Grand Theft Auto and related games in a greater effort to reduce Chicago carjackings, thus spawning H.B. 351.[5] The bill was filed on February 19th, and was referred to the Rules Committee on February 22nd after its first reading.[6]

The amendment itself aims to prohibit the sale of violent video games to anyone and modify two definitions within 2012’s Violent Video Game Law in Illinois’s Criminal Code: 1, violent video game; and 2, serious physical harm.[7] The former’s new definition would include “a video game that allows a user…to control a character…that is encouraged to perpetuate human-on-human violence in which the player kills or otherwise causes serious physical or psychological harm to another human or an animal.”[8] H.B. 351 would also alter the definition of “serious physical harm” to “psychological harm and child abuse, sexual abuse, animal abuse, domestic violence, violence against women, or motor vehicle theft with a driver or passenger present inside the vehicle when the theft begins.”[9]

All three proposals embedded within the bill are receiving staunch criticism from the public and legal scholars, as the restrictions on video game speech clash with First Amendment protections and are too ambiguous for proper administration of the law. Supreme Court precedent has long held that video games qualify as protected speech under the First Amendment and that speech about violence is not necessarily obscene, an exception to First Amendment protection.[10] In Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, the Supreme Court struck down a California state bill which prohibited the sale of violent video games to minors, rejecting California’s argument that preventing the violence caused by violent video games was enough of a compelling government interest to pass strict scrutiny.[11] In fact, studies have shown that there is no cognizable link between violent video games and real life aggressive, argumentative, or violent behavior—further weaking any state’s argument for restricting violent speech in video games.[12]

Further, the proposed broadened statutory definitions within the Violent Video Game Law do not set a clear enough standard for video game developers to know whether their games will be restricted. The new definitions aim to restrict games that “encourage human-on-human violence,” but would more sprite-based and less-realistic video games with combat elements be restricted? Do fighting games like Street Fighter and Tekken meet this definition? Would a cutscene depicting a character’s traumatic past be banned in Illinois for portraying “psychological harm… [or] sexual abuse[?]”

While regulating overly violent and obscene content is important to the wellbeing of society, Illinois’s H.B. 351 will likely be another failed attempt at restricting people’s access to violent media. Video game content regulations are better left to the self-regulatory bodies of the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), which provide content indicators for parents and consumers to make informed purchasing decisions.

[1] Zac Cligenpeel, Ban sale of Grand Theft Auto, other violent video games, state rep says, Chicago Sun Times (Feb. 22, 2021) https://chicago.suntimes.com/news/2021/2/22/22295471/grand-theft-auto-illinois-ban-violent-video-games-carjackings-evans-operation-safe-pump.

[2] Sun-Times Wire, Chicago sees 51 homicides in January—highest in 4 years, Chicago Sun Times (Feb. 1, 2021) https://chicago.suntimes.com/crime/2021/2/1/22261431/chicago-murders-51-homicides-january-highest-four-years.

[3] Christine Hatfield, Illinois Video Game Ban Bill Faces Uphill Legal, Scientific Battles, WGLT (Mar. 8, 2021) https://www.wglt.org/post/illinois-video-game-ban-bill-faces-uphill-legal-scientific-battles#stream/0

[4] Mitch Dudek, In effort to thwart carjackings, private security firm to post guards at gas stations, Chicago Sun Times (Jan. 22, 2021) https://chicago.suntimes.com/news/2021/1/22/22244743/carjackings-private-security-firm-guard-gas-stations-early-walker-william-kates.

[5] Cligenpeel, supra note 1.

[6] Bill Status of HB3531, Ill. Gen. Assemb., https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/BillStatus.asp?DocNum=3531&GAID=16&DocTypeID=HB&SessionID=110&GA=102 (last visited Apr. 1, 2021).

[7] H.B. 351, 102nd Gen. Assemb. (Ill. 2021).

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Brown v. Ent. Merchants Ass’n, 564 U.S. 786 (2011).

[11] Id.

[12] Dmitri Williams & Marko Skoric, Internet Fantasy Violence: A Test of Aggression in an Online Game, Communication Monographs (June 2005) http://dmitriwilliams.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CMWilliamsSkoric.pdf.