By: Matthew Bade

On October 12th, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Andy Warhol Foundation, Inc. v. Goldsmith.[1] This is the first fair use case to come before the Court since its ruling last year in Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc. and will likely clarify the extent of the Court’s decision in that case.[2] A holding in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation could further expand the scope of fair use, while a holding in favor of Goldsmith would seemingly walk back the Court’s ruling last year.

Fair use of a copyrighted work is an exception to normal copyrights and a defense against copyright infringement.[3] The Copyright Act codifies a four factor test to determine whether use of a copyrighted work constitutes fair use: (1) “the purpose and character of the use;” (2) “the nature of the copyrighted work;” (3) the proportion of the copyrighted work used; and (4) the market effects of the use.[4] Under the first factor, whether a particular use is transformative is a key consideration and is potentially dispositive.[5] Prior to Google, a transformative use was one that “adds something new,” rather than merely copying and superseding the original work.[6]

However, in Google, the Court held that directly copying some 11,500 lines of API code was transformative and constituted fair use.[7] In expanding the scope of transformativeness and thereby widening the bounds of fair use, the Court’s opinion drew a distinction between software and non-software copyrights.[8] Now the Court is being asked to rule on whether this new definition is applicable to copyrighted works beyond software.

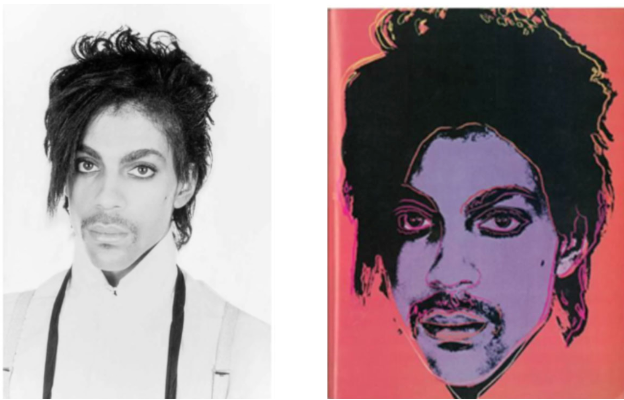

In 1981, professional photographer Lynn Goldsmith took a series of photographs of the musician, Prince.[9] In 1984, Goldsmith licensed one of these photographs to Vanity Fair for use as an artistic reference for a work by Andy Warhol.[10] In addition to the authorized work produced for Vanity Fair, Warhol also created a series of 15 additional images based on Goldsmith’s photograph.[11] It is these images that are at the center of the copyright infringement case brought by Goldsmith, which now hinges on whether Warhol’s use of the Prince photograph was transformative.[12]

Although the district court granted summary judgment in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation, the Second Circuit reversed, concluding that Warhol’s images were not transformative and that the remaining factors favored Goldsmith.[13] Critically, the Second Circuit’s holding uses visual similarity as the basis for evaluating transformativeness.[14] In doing so, the Second Circuit created a circuit split with the Ninth Circuit, which has held that a work is transformative “as long as new expressive content or message is apparent” even when it “makes few physical changes to the original.”[15]

The Andy Warhol Foundation appealed the Second Circuit’s decision, citing the Supreme Court’s decision in Google and the circuit split, and is now awaiting oral arguments.[16] In the meantime, this case has attracted a large number of amicus briefs from industry and labor groups, artists and authors, members of the Senate, the Solicitor General, and even a science fiction fan club.[17] Whatever the outcome, the wide attention reflects the case’s potentially far-reaching effects across the entire creative and entertainment industry.

[1] SCOTUSblog, https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/andy-warhol-foundation-for-the-visual-arts-inc-v-goldsmith/ (last visited Oct. 2, 2022); Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 11 F.4th 26 (2d Cir. 2021), cert. granted, 142 S.Ct. 1412 (U.S. Mar. 28, 2022) (No. 21-869).

[2] U.S. Copyright Off., https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/fair-index.html (last visited Oct. 2, 2022).

[3] 17 U.S.C. § 107.

[4] Id.

[5] Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 579 (1994) (“the more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors”).

[6] Id.

[7] Google LLC v. Oracle Am., Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1183 (2021).

[8] Id. at 1208-09 (“The fact that computer programs are primarily functional makes it difficult to apply traditional copyright concepts in that technological world. … As such, we have looked to the principles set forth in the fair use statute, § 107, and set forth in our earlier cases, and applied them to this different kind of copyrighted work.”).

[9] Goldsmith, 11 F.4th at 33.

[10] Id. at 34.

[11] Id.

[12] Id. at 35-36.

[13] Id. at 51.

[14] Id. at 42-43.

[15] Seltzer v. Green Day, Inc., 725 F.3d 1170, 1177 (9th Cir. 2013).

[16] Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 11 F.4th 26 (2d Cir. 2021), cert. granted, 142 S.Ct. 1412 (U.S. Mar. 28, 2022) (No. 21-869).

[17] SCOTUSblog, https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/andy-warhol-foundation-for-the-visual-arts-inc-v-goldsmith/ (last visited Oct. 2, 2022).